Expanding the education voucher system

By Jam Magdaleno and Cesar Ilao III

LAST MONTH’s release of the final report of the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM II) stands as a culmination of years of policy debates needed to rescue the country’s education system from creeping irrelevance. Thankfully, the report signals serious openness to expanding the education voucher system, which currently covers only senior high school students. The report’s timing is especially significant, as the expansion of the education voucher system has now been included in the Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council’s (LEDAC) priority legislative agenda.

A simple word count into the 634-page report, “Turning Point: A Decade of Necessary Reform (2026–2035),” reveals something telling: the word “voucher” appears 54 times.

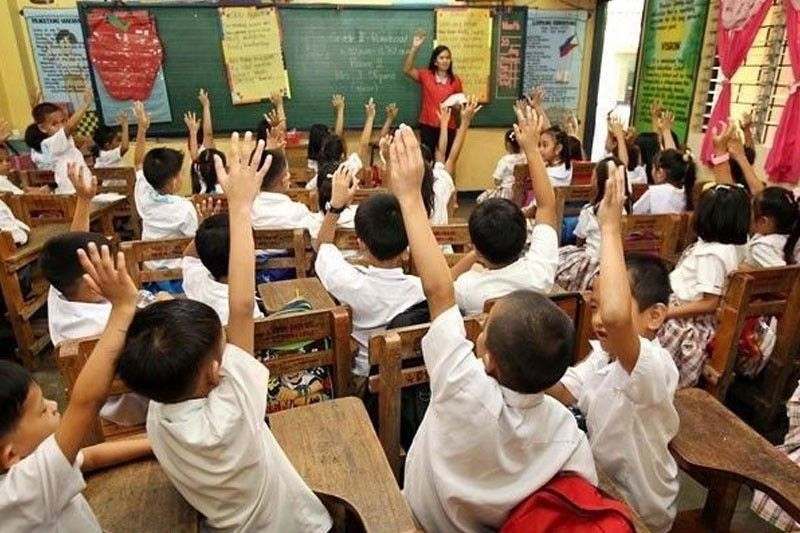

The urgency of expanding the voucher system under the Government Assistance to Students and Teachers in Private Education (GASTPE) program has become undeniable. Our public schools remain congested. Classroom construction is slow, and reports of overpriced or substandard facilities periodically surface. For the 2025-2026 school year, the Department of Education (DepEd) faces a staggering shortage of 165,000 classrooms and more than 56,000 teachers to serve a projected 27.6 million enrollees.

At the core of this crisis lies a fundamental logic of information asymmetry, which economists refer to as the “knowledge problem.” Simply put, central planners (government bureaucracies) do not possess the ability to harness the dispersed and rapidly changing (tacit) knowledge embedded in millions of individual decisions made daily, in this case, by parents, students, and schools.

Whenever proposals for large-scale public classroom construction are floated, the “knowledge problem” stands as a warning: When the state attempts to forecast demand, allocate supply, and micromanage outcomes from the center, the informational burden quickly becomes overwhelming, and, in practice, paralyzing. DepEd, the country’s largest government agency with approximately one million employees, must correctly predict enrollment shifts across thousands of municipalities, determine where classrooms are needed most, bid out contracts, supervise construction, and monitor compliance.

This explains why shortages persist in some areas while facilities remain underutilized in others. Procurement controversies, from overpriced, substandard school buildings to chronic construction delays, are a result of decision-making detached from the information that matters most: local demand, school-level conditions, and family priorities.

This doesn’t mean government intervention should be abandoned. It means that some forms of intervention are structurally better suited to overcoming informational limits than others.

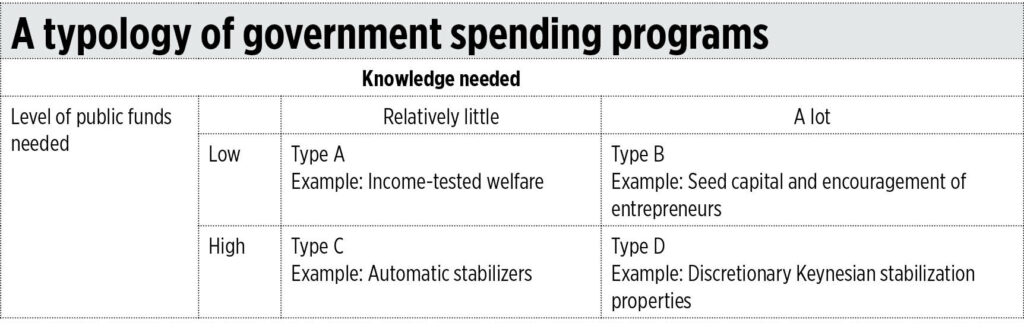

To explain our point better, we refer to a useful framework by Swedish economist Andreas Bergh. He classifies government programs along two dimensions: fiscal size and knowledge intensity (see the table). Programs that are large and knowledge-intensive are the riskiest. Programs that are large but knowledge-light — because they rely on decentralized decision-making — are likelier to succeed and be sustainable.

To ground this in our context, we will use two examples: the voucher system and the free tuition law.

Using Bergh’s typology above, we can surmise that education vouchers fall under Type C intervention: they are fiscally significant, yet they minimize the knowledge burden on the state.

This stands in stark contrast to Type A programs (low-cost, low-knowledge income transfers) and Type B programs (modest-cost but high-knowledge industrial “winner-picking”). On the other hand, the free tuition law falls under the high-risk Type D programs (expensive, knowledge-intensive macroeconomic fine-tuning).

Under the voucher system (Type C), the government finances the student, but families and schools — those closest to the relevant information — handle the complex decisions of enrollment and quality assessment.

Consider a student whose parents know that the nearby public school has 50 students per class, while a private school a few kilometers away maintains 25 and offers remedial reading support. They also know the true travel time, safety of the route, and whether the schedule fits their work hours. Localized realities like class size, support programs, commute constraints are information parents possess immediately but which no central planner can efficiently process at scale.

By contrast, the large-scale, centralized expansion of public school infrastructure is notoriously knowledge-intensive. Planners must predict precisely where to build, how much capacity to create, and how resources should be distributed across thousands of heterogeneous communities. This assumes demand forecasts will be accurate, and adjustments can be made in real time.

The same informational limits appear in higher education policy. Findings from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) shows that the Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act (the free tuition law) disproportionately benefits students from better-off households. These students are more likely to have the resources to complete senior high school and, crucially, the academic preparation to pass competitive admission standards in state universities.

A universal subsidy doesn’t distinguish between the haves and the have-nots. In economic terms, this leads to resource misallocation arising from informational constraints. In plain language, it means public funds end up providing a “free ride” to individuals who could have afforded tuition anyway.

Vouchers operate on a different logic. Because the state is not locked into a single delivery mechanism, assistance can be directed toward students in overcrowded schools or poorer municipalities. This places school choice in the hands of families who best understand their circumstances.

A MARRIAGE OF EFFICIENCY AND EQUITYThe decentralized nature of educational vouchers also speaks to a longstanding tension in economics: the tradeoff between efficiency and equity. Rather than forcing policymakers to choose between fiscal prudence and social justice, a well-designed voucher system marries both goals.

By granting the decision to students and their parents to choose their schools, the voucher system achieves efficiency. From a fiscal perspective, supporting students in existing private schools is frequently cheaper than expanding public provision. Building classrooms and hiring permanent staff create long-term financial obligations. Vouchers allow the government to tap into existing capacity without locking itself into rigid commitments. This comes at an opportune time when many private schools are suffering from low-employment due to the mass exodus of students to public schools.

Studies cited in legislation proposing voucher expansion estimate that accommodating excess learners through public school expansion would cost P3.7 trillion over 30 years, while expanding vouchers would cost P2.6 trillion — saving P1.1 trillion. That fiscal gap is not trivial. It represents resources that could be redirected toward teacher training, curriculum improvement, or early-grade literacy interventions.

Equity gains are equally important. Rather than providing a blanket subsidy to all students regardless of income status, vouchers increase the likelihood that students from poor households and overcrowded public schools can access better learning environments.

In a 2025 PIDS paper, “Strengthening and Expanding Government Assistance for Private Education,” the authors cite evidence showing that students in private schools tend to perform better than their public-school counterparts, even after controlling for socioeconomic background.

On average, private institutions operate with smaller class sizes, stronger school-level management, and greater instructional flexibility — conditions that are consistently associated with improved learning outcomes. Over time, these gains accumulate. Students who master foundational skills early are less likely to drop out and more likely to succeed in higher education and work.

TIMING MATTERSIf vouchers improve access, efficiency, and learning at the senior high school level, restricting them to just the final two years makes little policy sense.

The logic of decentralized choice (what we identified earlier as a Type C intervention) does not magically apply only when a student turns 16. If anything, it is most compelling in the early years, when foundational skills are formed and when families make the most consequential educational decisions.

By Grade 11, the die is often cast. EDCOM II’s stark finding that only about four out of every 1,000 senior high school students pass expected learning standards underscores how deep the gap runs. Deficits in literacy and numeracy do not pop up overnight; they emerge in the primary grades and metastasize over time.

Trying to fix a decade of accumulated disadvantage with a two-year voucher is like applying a band-aid to a fracture. Expanding vouchers to the elementary and junior high levels allows the system to adapt sooner. It enables targeted access before congestion intensifies and, crucially, before inequality compounds.

There is also a glaring asymmetry here that we rarely acknowledge: Wealthier families exercise school choice from Grade 1. They do not wait for the government’s permission to seek better learning environments for their children. Poorer families, by contrast, are effectively locked into under-resourced public schools until the final stretch of basic education. Delaying vouchers is tantamount to widening this “choice gap.” Thus, to expand the voucher system is merely to follow the logic with which it was pursued in the first place: to allow decentralized actors — parents and schools — to process information early, not after the damage has already been done.

Education vouchers are not a silver bullet. In public policy, nothing really is. What we aim to demonstrate here is that, in light of the knowledge problem, an expanded voucher system can work. There are additional arguments in its favor: it is less prone to politicized decision-making and encourages public–private complementarity. At present, the education crisis demands a 634-page set of corrective measures, and its repeated calls for voucher expansion warrants a swift legislative approval.

Jam Magdaleno is head of Information and Communications at the Foundation for Economic Freedom (FEF) and an Asia Freedom fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and King’s College London. Cesar Ilao III is a researcher and communications specialist for FEF. He is a lecturer at the University of the Philippines and was formerly a researcher at Monash University, Australia.